Potemkin Village

Return to Articles

The curious case of a Wisconsin canton and its legally sanctioned “Swiss” architecture.

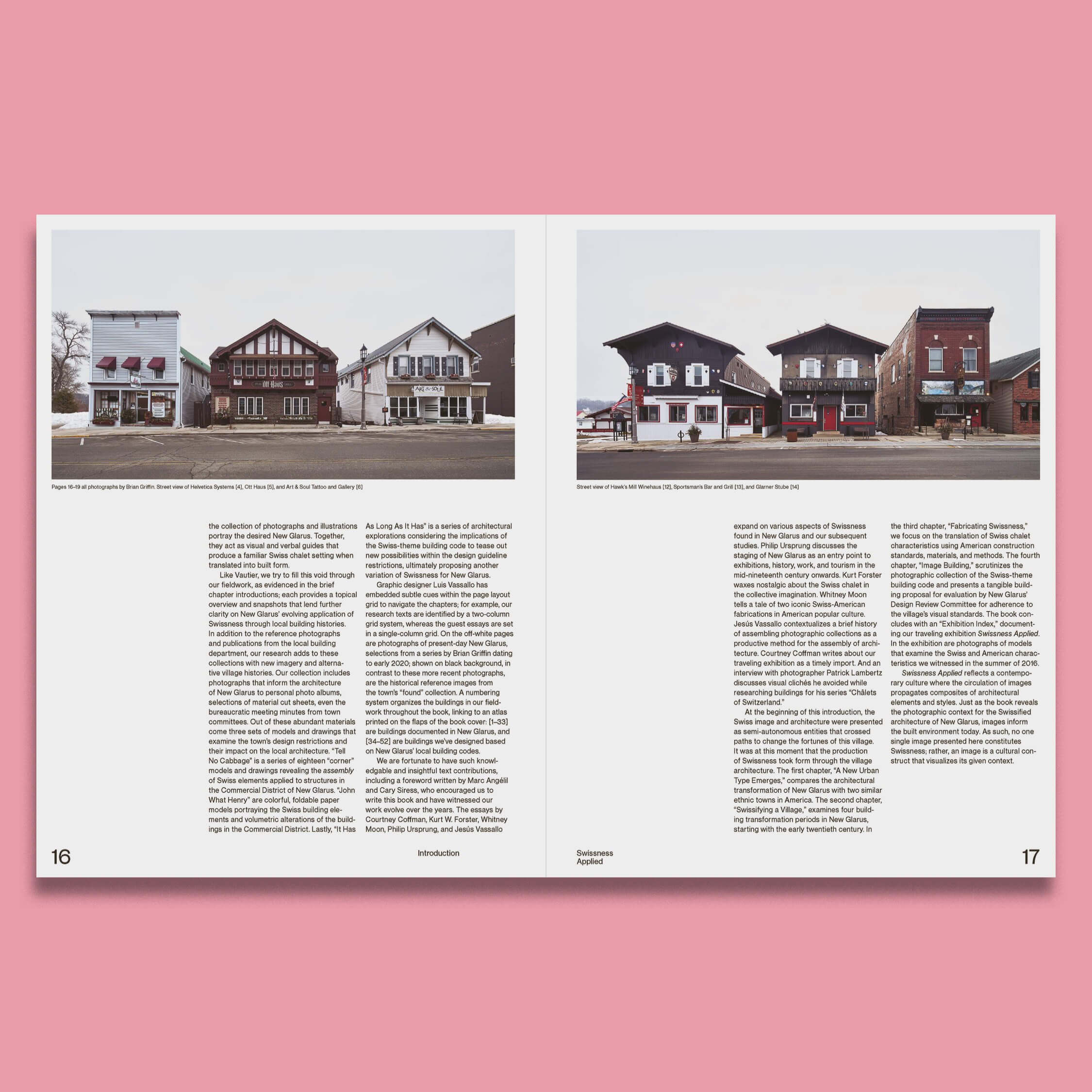

A sampling of the “Swiss” architecture of New Glarus, Wisconsin. Photography: Brian Griffin

My first project in architecture school was an exploration of the cube. The semester comprised a series of exercises meant to introduce us to architecture slowly and methodically. We graduated from lines to planes, and then to volumes, a progression that culminated in the cube (foremost among the Platonic solids as far as our modernist teachers were concerned). We drafted our cubes in graphite, guided by Mayline and triangle—all right angles, after all—drawing on precious Strathmore paper. (Cost: five dollars per sheet.) The paper’s surface was blinding white and pillow soft; we soon found it was apparently engineered to record every smudge and capture every errant fingerprint like incriminating clues left at a crime scene. And no use trying to cover our tracks—even my eraser left slick marks on the page. We learned to avoid any contact with the paper at all, a difficult task, especially so once we began to build models from the very same sheets. I presented one such cube during a pin-up toward the end of the semester. My critic—diligent, straitlaced, Yale-trained, he was a star pupil of both Zaha Hadid and Robert A. M. Stern—picked up my maquette, 6 inches on each side, or at quarter-inch scale, 24 feet per edge. He peered through its tiny apertures, noting the subtle correspondences among facades that I had worked so hard to inscribe. He looked closely for some time, grinned, then offered his thoughts: “It’s hard to criticize—it’s so good, but so elegant as to be almost boring,” he said. “It’s so … Swiss.”

“Fine by me,” I thought at the time. Thinking back on it, I still wonder what qualifies something as being Swiss. Is it synonymous with precision and craftsmanship? A byword for wealth and exclusivity? Is it an affect? The impenetrability, neutrality, even aloofness that is evoked by the work of Swiss superstars like Peter Zumthor and Valerio Olgiati?

Nicole McIntosh and Jonathan Louie of Architecture Office have other ideas. The duo, who recently relocated to Zurich (McIntosh’s birthplace), published Swissness Applied: Learning from New Glarus (Park Books) late last year. The book grew out of their traveling exhibition of the same name. Exhibited to critical acclaim in New Haven, Boulder, Milwaukee, and Güterschuppen, Switzerland, from 2019 to 2021, the project ambitiously explored “how cultural imaginaries are appropriated and reconstructed” by and through architecture. Though centered on the town of New Glarus in Wisconsin, founded by Swiss migrants in the middle of the 19th century, their research considers our field’s broader imbrication with histories of migration, identity, economy, and construction in other places as well. (In addition to New Glarus, the book includes documentation of transplant architectures in migrant-founded communities, including Frankenmuth, known as Michigan’s “Little Bavaria,” and Solvang, California’s “Little Denmark.”)

Swissness Applied began as an exhibition at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Photography: Brian Griffin

The project is animated by the unresolved tensions between a supposedly authentic but elusive idea of Swissness (“real” Switzerland) on the one hand and allegedly inauthentic but ubiquitous clichés of Swissness on the other (cheese, chocolate, chalets, and so on). But as McIntosh and Louie demonstrate, the concept becomes most fascinating in practice—that is to say, when Swissness is, per their title, applied.

Notions of Swissness serve different purposes and take on different meanings at different times. New Glarus, for instance, was settled by impoverished farmers whose colonial expedition to the New World was funded by their canton (old Glarus). But Swiss-style design played no major role in the new town’s architectural identity until after World War II. Facing deindustrialization at mid-century—a “Helvetia”-brand condensed milk plant, the town’s largest single employer since 1910, closed in 1962—New Glarus pivoted to the tourist economy soon thereafter. In short, it was economic blight that drove New Glarus’s settlers out of Switzerland in the first place, and it wasn’t until economic circumstances changed again that the town began to self-consciously cultivate its Swissness.

Swissness Applied: Learning from New Glarus, edited by Nicole McIntosh and Jonathan Louie of Architecture Office. (Courtesy Park Books)

Identity is constructed, always built with materials from many sources, some inherited, some acquired, and others repressed. In this case, “Swissifying” New Glarus meant cultivating and memorializing the town’s roots. Already more than 100 years old by the time the plant closed, the town made itself over as Swiss for the sake of heritage tourism while disregarding the more unsavory moments in the history of the place. As is briefly noted in the book, the town was settled on land stolen from Native tribes of the Ho-Chunk Nation, displaced in 1829. Swissness—like any heritage and any telling of a history—can obfuscate. Understanding a place requires first learning to look at it carefully.

Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour’s Learning from Las Vegas (1972) looms large over McIntosh and Louie’s project, a fact they wear proudly on their sleeves. (Their subtitle is a loving homage.) There are many references to ducks and decorated sheds. (New Glarner buildings tend to be examples of the latter.) There are careful orthographic drawings of nonpedigreed architecture and deadpan photographs of storefronts taken from the roadside. (Brian Griffin’s engrossing portraits of New Glarus’s downtown are sublime.) There are scale models that faithfully reproduce charming architectural idiosyncrasies. (Several buildings sport ornate Swiss fronts that jarringly adjoin blank side elevations.) These documents are, without fail, fascinating. Swissness Applied is a master class in architectural fieldwork and close reading. It shows that there is still gas left in the tank, so to speak, of an approach that is now more than five decades old.

In addition to the Milwaukee exhibition (pictured above), McIntosh and Louie have staged shows at the Kunsthaus Glarus in Switzerland as well as the Yale School of Architecture and the University of Colorado. Photography: Brian Griffin

McIntosh and Louie are incisive researchers. They ask probing questions of their subject. Some of their inquiries are historical in nature. They explore “how the heritage of a place manifests elsewhere” and they ask how traditions of architectural ornament, among other aspects, evolve and mutate when transposed. Other lines of research are more prosaic. For instance, how do you build a timber chalet out of dimensioned lumber and modern building products? Just as there is no essential, ideal Swissness, there is no single formula that captures this émigré architecture in all its depth. The answers, if there are any, coalesce in the rich complexity of buildings—the book documents a tavern, a hotel, and a convenience store, among several other Swiss-style structures—that are called upon to be not only bearers of cultural history but also vital equipment sustaining the local economy. In a perverse, kitschy way, New Glarus might be one of the few towns in the United States that understand the full value—both social and economic—of their architecture.

Here, Swissness is enforced with the authority of government by the town’s Design Review Committee, the book’s most-often-invoked protagonist. Any new construction, significant alteration, or renovation must adhere to the town’s “architectural theme,” an ordinance inscribed in the local code in 1999. On paper it is a formal set of straightforward architectural controls—e.g., that roof pitch must fall somewhere between 31⁄2 and 51⁄2—and is in any event subject to the final discretion of the committee. The other, somewhat more mysterious element of the legislation is a set of reference photographs of Swiss buildings held in the municipal offices but apparently rarely consulted. As McIntosh and Louie divulge, it is not clear who selected the official photographs, nor even where the buildings they depict are located. It is a loose archive of decorated facades, window boxes and wood-shuttered windows, picturesque roofs, and half-timber framing. It is a collection of details that add up to a bureaucratized, phantom ideal of Swiss architecture, or to put it another way, a set of Swiss organs in search of a Swiss body.

An elevation study depicting New Glarus before (top) and after (bottom) the municipal design ordinance went into effect. Courtesy Architecture Office .

In practice, the requirements of the Swiss architectural theme have sometimes led to truly bizarre architectural misadventures. A case in point: a concrete gas station turned into a retail outlet. Formerly known as the Swiss Shoppe, and before that the Schoco-Laden (a droll pun on the German words for “chocolate” and “shop,” respectively), it is now the Maple Leaf Cheese and Chocolate Haus. It has the local distinction of being, as McIntosh and Louie note, “the only building transformation to prop up an entire roof—and an unoccupiable floor—atop the original structure.” As the authors show in drawings of forensic detail, the faux second floor includes a balcony and windows, but neither stair access nor insulation is provided. This curious building illustrates the misfit that emerges as legible emblems of Swissness lose the conventions of materiality and construction that were traditionally attached to them. When the two become delaminated and reassembled by other means, as they do throughout New Glarus, what emerges is a charming Potemkin Swissness that cannot be mistaken for the real thing, but satisfies the requirements of code to a T and is, in its own way, delightful, “almost all right,” even.

The gas station underwent Swissification in 1981 at the hands of Stuart Gallaher, a local architect who has made something of a cottage industry (or a chalet industry, as the case may be) of designing Swiss-style architecture in New Glarus. If I have one complaint about McIntosh and Louie’s project, it is that we never learn much about the local personalities who contributed to this place. Gallaher, we’re briefly told, made several study trips to Switzerland so that his buildings could be “as authentically Swiss as possible in every detail,” but the rest of his biography is left unexplored. About the oft-cited Design Review Committee, we have little sense of its composition.

As anyone who has spent time in a small town knows, drama and gossip are inevitable facets of everyday life. It’s unlikely that Swissness was ever applied in New Glarus without some friction. Curiously, human figures appear in only a handful of the publication’s 280 remarkable illustrations. Despite the curious absence of the human element—or perhaps because of it—the book remains laser-focused on the architecture. And why should any architect complain about that?

Spreads from Swissness Applied: Learning from New Glarus. Courtesy Park Books.